Many of us are making a big mistake. Because of our deep desire for consistency we wind up making horrible investing decisions.

Specifically, booking profits too soon (because we want to be right, feel smart and/or not give back whatever gain we currently hold). The fancy term for this is called the Disposition Effect.

Contrary to what many of us think, consistent long-term investing performance is built on a foundation of a very few but very large winners, not an abundance of small winners (something most of us wish was the case). Even Berkshire Hathaway has made most of its money in only a handful of investments.

The best opportunities don’t come around very often, so you cannot afford to miss them when they do.

Sports, as well as many other areas of life, supports the notion of succeeding with a small win-percentage as well. The best hitters only have a .300 average. The best QB’s only score on a small fraction of their drives. The best hockey players have ~12% shooting percentage.

The best teams do not have a full roster of superstars, but only 2-3. The Bulls had Jordan and Pippen. The Yankees had Jeter and Rivera. The Penguins had Crosby and Malkin. The Patriots had Brady and Belichick. The best teams only need a few great players to succeed.

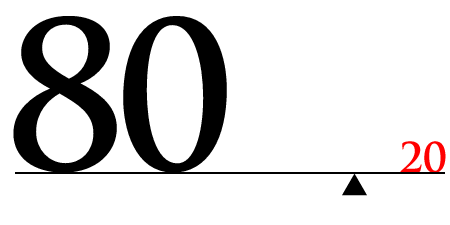

I’m sure by now everyone is familiar with Roger Federer’s speech at Darmouth where spoke of his career statistics — winning 80% of his matches, but only 54% of the points. Shocking to many, but this is how it works.

Thinking you need to win 80% of the points to succeed is incorrect and indeed where many of us go wrong.

Taking Pareto to the Extreme

To show you just how embracing the Pareto Principle can help you win in the markets, I ran an experiment.

I recently simulated the results of a simple trend-following trading system from 1980 to today. It generated 8,600 trades.

What percentage of the trades do you think were profitable?

What percentage of the trades netted out even when summed up (no gain or loss)?

What percentage of the trades accounted for 80% of the system’s total profit?

Back when I was building my firm, I did a lot of this kind of work. Coming from a life of baseball, I saw many similarities to Trend-Following. Maybe this is what attracted me to it in the first place and why I became comfortable with it. Low win rates, pitching, defense and the 3-run homerun proved to be a viable long-term winning formula.

The answers to the three questions above were shocking then and they’re shocking now. The answers: (1) 42.6%, (2) 99% and (3) 0.34% (30 out of 8,600).

Only 42.6% of the trades were profitable. 99% of the trades netted to no gain at all. And only 0.34% of them accounted for 80% of the total gain. Absolutely nuts.

Surely these are not the stats of a strong and consistently performing strategy, right?

What percentage of the 535 (1/80-6/24) months do you think produced a positive return? Answer: 62%. And what percentage of the 44 years produced a positive return? Answer: 80%.

The CAGR of this system was 15% with an annualized volatility of 14.5% and worst loss of -24.2% [Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results]

Huh? Wha? How?

The beauty of Pareto’s Principle, and maybe why it works in the markets, is that it’s counterintuitive and doesn’t feel particularly good. Who wants to make a living on the back of a small win-rate and infrequent large winners? Not many as it turns out.

The Best Trades Tend to Come When Your Guard is Down

In the graph below, I show the top 15 performing trades for this trend-following system. You tend to have to enter them when recent performance has been negative and not feeling particularly confident.

A Minority of Months Account for Most of the Return

Similar to the sample trends-based system above, the majority of the total return in different asset-classes tend to come in a small percentage of time.

Take a look.

U.S. Equities

Real Estate

U.S. 10-Year Note

Commodities

The Best Returns Tend to Come During Losing Periods

For buy-and-hold investors, arrogance/greed during bull markets tends to turn into fear/despair during bear markets. Die-hard buy-and-holders tend to second-guess the approach when losses pile up. There’s nothing like recent losses that get people to abandon their belief system.

If you’re going to buy-and-hold any asset-class, you must know that losses are part of the deal. Also, that bailing out during losing streaks can inflict irreparable harm on your performance. One or two mistakes can make all the difference.

Remember back in 2008-09? How many of you sold at least some of your equity funds during that time? When did you get back in? DID you get back in? And if you did, how much did you buy?

Most people didn’t get back in for years (when the feelings/fear of the Financial Crisis wore off) despite many equities making new highs in Q3-4 2009. As a result, they missed a ton of upside. No buy-and-holder can afford to miss top these months.

Here’s a look at the top performing months over time for major asset classes. On average, the best months tend to come when recent performance has been negative.

U.S. Equities

Real Estate

U.S. 10-Year Note

Commodities

Learn to Love Pareto’s Principle

You can win over the long run with lots of small losses and a few large winners. To pull this off, however, you need to embrace cutting losses (admitting you’re wrong so you can stay in the game) and riding winners (to pay for all of the small losses and then some).

Playing the opposite way, the anti-Pareto way, is to favor your ego over the evidence of superior sports teams, companies or investment firms.

Great article! Thank you!

This it the best article I have read in years. Extremely enlightening.